IntOGen Agent - Methodology

Introduction

Cancer genome sequencing has produced extensive catalogs of somatic mutations, and driver discovery methods now scan these data for signals of positive selection. These methods test whether the observed pattern of mutations in a gene departs from what would be expected under neutral mutagenesis, thereby nominating genes whose mutations are likely to confer a selective advantage. Frameworks such as intOGen [1] aggregate multiple driver discovery algorithms and tumor cohorts to deliver robust lists of candidate cancer genes across many tumor types. However, these driver catalogs by themselves do not explain how each gene contributes to tumorigenesis, nor do they provide a consistent, reference-backed synthesis of the supporting literature for each specific gene–cancer pair.

Bridging this gap typically requires expert manual search of the literature and biological knowledge bases, filtering the information and synthetizing it. For any given candidate driver, a domain expert must: (i) interpret basic gene and protein function; (ii) sift the literature for cancer-type–specific alteration patterns and mechanisms; (iii) reconcile heterogeneous evidence across model systems and cohorts; and (iv) document the conclusions with well-structured references. These complications are compounded by the fact that cancer driver genes have very different cellular and molecular functions. Therefore, performing this process at scale for hundreds of genes and multiple cancer types is time-consuming, error-prone, not reproducible, and the results for different driver genes may be very disparate. In consequence, mechanistic interpretation often lags behind statistical driver discovery. Bridging this gap is essential to advance our knowledge of the mechanisms of tumorigenesis and translate the discovery of cancer driver genes and mutations to targeted personalized anti-cancer therapies.

To address this, we developed an AI multi agent–based workflow that takes as input lists of genes under positive selection—i.e. intOGen driver predictions—and produces structured, citation-backed synthetic descriptions of literature knowledge (including mechanistic data) of their involvement in specific (or any) cancer types. The multi agent system combines Large Language Models (LLM) with Model Context Protocol (MCP) tools for gene metadata, protein annotation, and literature retrieval. Using OpenAI models for both reasoning and tool orchestration, the system automatically gathers literature evidence, and normalizes and validates references. It produces three main human-readable outcomes. The first is a short report summarizing the core gene/protein functions. The second is an assessment of whether literature evidence exists of the involvement of the gene in the tumor type in question. The third outcome (produced only in the cases that the prior assessment is positive) is a synthesis of the literature evidence on plausible mechanisms of action of the gene in tumorigenesis.

Methods

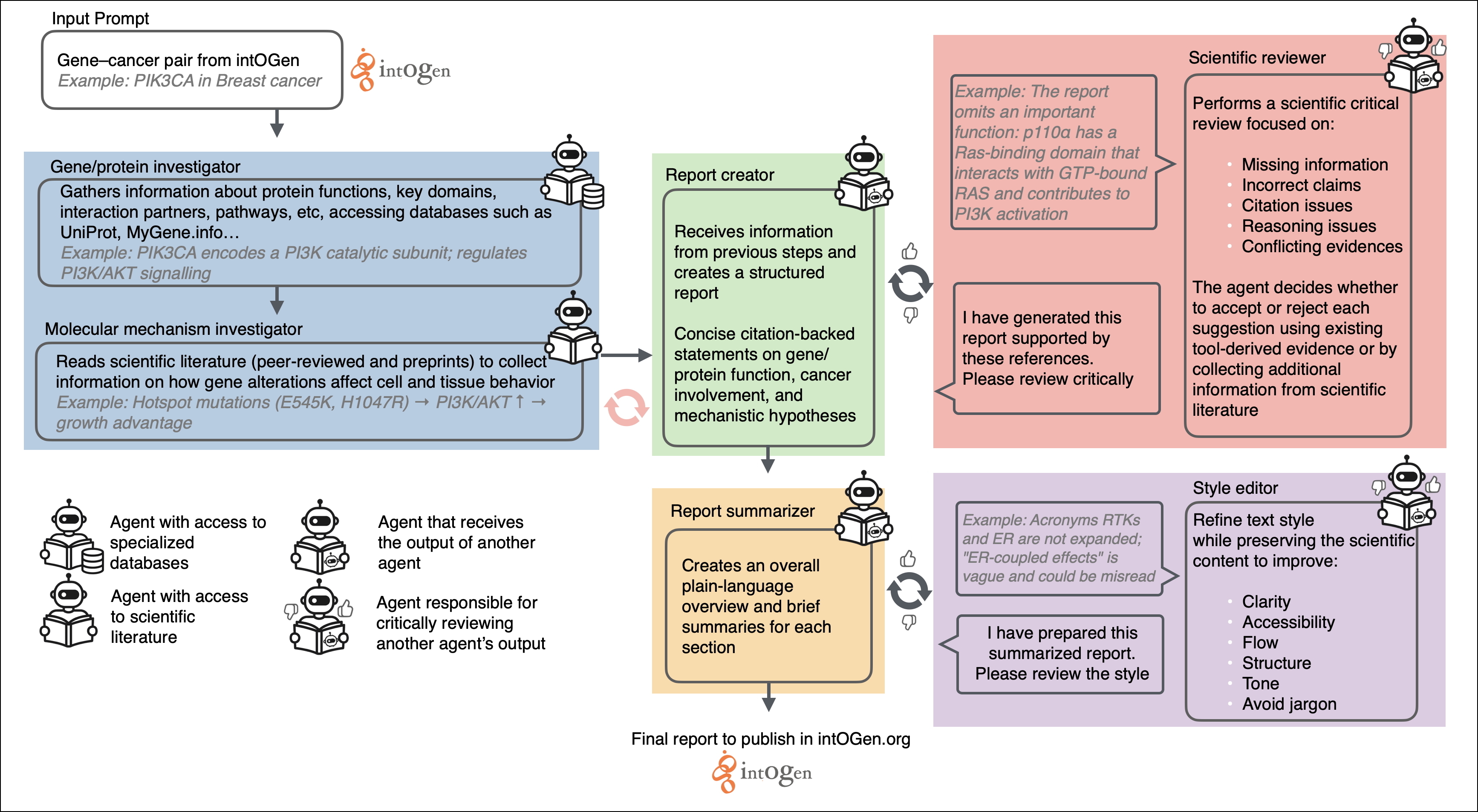

We developed intOGen Agent, an automated, AI-based multi-agent workflow that converts lists of intOGen driver calls into structured, literature-supported explanations of how each gene may contribute to tumorigenesis within a specific cancer type. intOGen Agent is implemented as a multi-agent system in which several specialized agents with distinct roles collaborate.

First, for every gene–cancer pair, two agents—a gene/protein investigator and a molecular mechanism investigator (integrating Large Language Models (LLMs) with Model Context Protocol (MCP) tools)—retrieve gene and protein annotations, survey the biomedical literature, and generate concise, citation-backed summaries describing biological function, cancer involvement, and plausible mechanisms of action. All information retrieved is used to write a report (report creator agent), which is summarized (report summarizer agent) to ease human readability. A “scientific reviewer” then evaluates each report and provides iterative critical feedback on its scientific content until no additional issues are identified or the maximum number of revision cycles is reached. Finally, a “style editor” reviews the summaries to improve clarity and readability. An overview of the full workflow is provided in Figure 1.

Cohort construction and run scheduling

We started from the list of gene–cancer type pairs identified by the intOGen driver discovery pipeline [1][2]. Each record was trimmed for leading/trailing whitespace, validated for non-empty fields, and deduplicated at the gene–cancer type pair level. For every unique gene, we added a corresponding “general cancer” (pan-cancer) task so that each gene was evaluated both in its specific tumor type context and for any tumor type.

Before launching new analyses, the workflow inspected existing output directories to identify completed gene–cancer type pairs. When a matching pan-cancer report was already present, the corresponding task was skipped. If a fully rendered gene–cancer type directory was available from a prior run, it was copied forward to avoid recomputation. The remaining tasks were distributed across an asynchronous worker pool: a single shared worker executed runs serially when parallelism was disabled, whereas higher-throughput modes spawned short-lived subprocesses so that each run held its own tool stack, environment, and log stream.

Model Context Protocol (MCP) tool environment

Tool access was provided through Model Context Protocol (MCP) servers, a framework that exposes external tools and databases to language models in a structured and auditable way, and was managed via the MCP Python SDK package [3]. For each worker, the configuration file (config.yaml) specified which MCP servers to start and how to connect to them. We used two MCP servers: UniProt MCP [4], launched from a configurable path prefix, and BioMCP [5], started via stdio. The controller established client sessions to each server, retrieved and cached tool schemas, and recorded the mapping between tools and servers to enforce strict allow-lists in later phases.

A structured asynchronous exit stack tracked all open transports and child processes. On completion of a run, the stack closed client sessions, terminated MCP subprocesses, and released any allocated ports in a defined order, ensuring clean shutdown and preventing resource leakage across runs.

Large Language Model (LLM) calls and tool orchestration (including MCP tool selection and argument construction) were handled via the OpenAI Python package [6], which provided both the base reasoning models and the tool-calling interface.

Phase 1: gene and protein function characterization

Phase 1 was designed to establish a mechanistic baseline for each gene. The LLM was placed in the role of a molecular oncology assistant with a system instruction focused on core gene and protein function, including domains, interactions, pathways, isoforms, and post-translational regulation.

Tool usage in this phase followed a fixed order:

-

Gene identifier resolution using a

gene_gettertool to retrieve canonical identifiers and aliases. -

Protein annotation retrieval via a UniProt-backed

search_by_genetool to obtain detailed functional annotations.

Where tools accepted an organism argument, “human” was used by default; if calls repeatedly failed or returned no usable content, a fallback to “mouse” was permitted. Each tool call could be retried up to three times with adjusted parameters (e.g., alternative identifiers) before the system recorded a structured failure and proceeded.

UniProt responses were post-processed with configurable parsing rules. For each category (isoforms, domains, motifs, subcellular locations, interactions, and post-translational modifications), the pipeline applied configurable caps controlling how many entries to retain, with a cap of zero effectively disabling that category. An include_sub_refs flag governed whether inline UniProt-specific references were preserved or stripped in the normalized output. These settings allowed users to tune the trade-off between completeness and concision. All raw payloads, along with timestamps and tool arguments, were persisted per run to support later audit and debugging.

Phase 2: cancer-specific evidence retrieval

Phase 2 focused on the involvement of the gene in tumorigenesis in a specified cancer type (or any cancer type if no specific tumor type is provided). At the start of this phase, the conversation state was reset and the LLM received a new system instruction emphasizing cancer-specific alteration patterns, mechanisms of action, and evidence for or against driver activity.

The tool routing map changed accordingly: UniProt access was disabled to avoid redundant queries, and a set of literature-oriented MCP tools (e.g. article search and retrieval functions) became available. The LLM was instructed to proceed in three steps: (i) generate internal hypotheses about plausible mechanisms based on the Phase 1 functional context; (ii) nominate “gold-standard” primary studies that should exist for each candidate mechanism; and (iii) use the literature tools to confirm, refine, or refute these hypotheses.

Queries were designed to combine gene symbols and aliases with cancer type names and mechanistic keywords (e.g. mutation type, copy number, epigenetic changes, pathway categories). Human data for the target cancer were prioritized, followed by closely related subtypes and then pan-cancer or model-system evidence. Tool calls in this phase also followed retry limits (up to two additional attempts with adjusted queries) before a failure was recorded and the analysis moved on. Null or contradictory results were explicitly recorded to allow later reporting of uncertainty or conflicting evidence.

Tool output summarization and reference management

All tool responses (functional annotations, literature abstracts, and full-text snippets) were processed by a dedicated summarization layer implemented with a compact LLM. For each tool call, the summarizer received the raw text and an “allowed identifier” list derived from previously observed references in the run (PubMed IDs, DOIs, ClinicalTrials identifiers, and database accessions). It returned oncology-focused bullet points that emphasized gene function, alteration patterns, and mechanistic links, while excluding background narrative, editorial text, or methods without relevant results. Every bullet was required to carry at least one citation.

Citations were normalized according to a strict contract. When PubMed links were present, they were converted to PMID form and preferred over equivalent DOIs or secondary URLs. When no approved identifiers were available for a given tool response, the summarizer labeled the evidence with a TOOL:<name> pseudo-identifier so downstream components could still track its origin.

In parallel, a reference manager scanned all raw tool payloads using regular expressions to extract PMIDs, DOIs, ClinicalTrials IDs, database names and accessions, and URLs. It merged duplicate identifiers across sources, prioritized authoritative links (PubMed over DOI over other websites), and enforced database-specific requirements (database references were retained only when both the source name and accession ID were available). For each identifier, the manager recorded the tool and call in which it first appeared, providing provenance for later auditing.

References that were later introduced directly into the report (for example during refinement) but had never passed through the reference manager were retained but explicitly flagged in the structured data model as “untracked” or lower-confidence. In the human-readable output, such references were annotated (e.g. with an asterisk) to signal that they had not been observed in the tool-derived evidence stream.

Structured report generation and Pydantic-based validation

After evidence collection completed, early system prompts and planning chatter were pruned from the conversation. The controller then issued a final instruction asking the LLM to return a single JSON object conforming to a predefined FinalReport schema. This schema defined three main sections—Gene/Protein Function, Assessment (including an involvement assessment), and, when appropriate, Mechanistic Hypothesis—plus a reference list and a detailed provenance block.

The JSON output was parsed and validated using Pydantic models [7]. Validation rules encoded in models.py included:

- Structural constraints

- Gene/Protein Function: 2–5 bullets, each 2–3 sentences, verb-first, and free of cancer-specific outcomes.

- Assessment: an involvement assessment (

supportedornot supported) plus 2–4 rationale bullets. - Mechanistic Hypothesis: 1–6 bullets only when involvement=

supported, each describing exactly one normalized chain of the form “alteration/state → mediator/pathway → cellular or clinical outcome”.

- Citation logic

- All bullets must reference at least one citation index.

- Citation indices must be 1-based and contiguous within the reference list.

- Every reference must be cited at least once; uncited references are rejected.

- References are ordered by first appearance across sections, and each bullet’s citation list must be in ascending order.

- Assessment and mechanism consistency

- The involvement assessment defaults to not supported unless pre-specified evidence thresholds are met.

- Setting involvement=supported requires that at least two rationale bullets collectively cite ≥3 references derived from ≥2 distinct sources.

- Mechanistic Hypothesis bullets are disallowed when involvement=

not supported. - Mechanisms are required to be non-redundant: bullets sharing the same normalized triple (cause, primary mediator, outcome) are merged during a final deduplication pass.

- Reference integrity

Referenceobjects validate identifier formats (including correct prefix for PMIDs, basic URL shape, and presence of bothdatabaseandrecord_idfor database entries).- When a PMID is present without a URL, a canonical PubMed URL is automatically derived.

- References that never passed through the reference manager are marked as untracked, enabling downstream consumers to distinguish tool-derived from manually added citations.

If parsing or validation failed, the controller triggered a controlled repair cycle: the LLM was asked to regenerate the report under the same schema constraints, with exponential backoff and a bounded number of retries. Only reports that passed Pydantic validation were accepted. For these, the curated reference metadata and provenance records were merged into the final object, and an oncology-focused markdown rendering was produced for human inspection.

Critic-driven scientific refinement

To improve scientific rigor, we implemented an optional critic loop. A separate LLM prompt, parameterized by the CritiqueReport schema, instructed the model to behave as a cancer genomics referee and to return structured feedback rather than free text. The critic evaluated four pillars: completeness and correctness of gene/protein function, coverage and accuracy of mechanistic hypotheses, alignment between Assessment bullets and the involvement assessment, and agreement of the assessment with broader literature consensus.

The CritiqueReport contained:

- A global gate (

overall_accept) and anoverall_score(0.0–1.0). - Optional per-section scores (gene function, mechanistic hypothesis, assessment alignment).

- A short narrative summary.

- A list of

CritiqueIssueobjects, each specifying:- the affected section (e.g.

gene_function,mechanistic_hypothesis,assessment,verdict_alignment) - a severity level (low/medium/high)

- whether the concern relied on information outside the current tool-derived evidence

- an explanation of why the issue matters

- a concrete recommended action (e.g. “locate canonical LOF study for this gene in colorectal cancer, suggested PMIDs…”).

- the affected section (e.g.

High-severity issues automatically set overall_accept=false and triggered a refinement phase. The refinement assistant received the previous FinalReport, the full tool history, and the CritiqueReport, and was instructed to revisit each critic item explicitly. When a concern could be resolved using existing evidence, the report was edited without additional tool calls. Optional new tool calls (again via MCP literature tools orchestrated through the OpenAI interface) were permitted only when enabled in the configuration and only for issues that could not be settled with already gathered data. Low-severity issues were never allowed to trigger new evidence gathering. After each refinement iteration, a new FinalReport was generated and re-validated; the critic loop continued until acceptance or until a maximum number of iterations was reached. Any unresolved high-severity issues at termination were recorded in the report’s provenance block.

Summary generation and style refinement

Following structural validation (and any scientific refinement), we generated plain-language summaries without citations. A dedicated “summary helper” prompt received the validated bullets for each section (Gene/Protein Function, Assessment, Mechanistic Hypothesis) and produced short prose summaries, an overall “headline” synthesis, and a role-of-action proposal (tumor suppressor, oncogene, context-dependent, or unclear) constrained to match the mechanistic content.

These drafts were then evaluated by a style critic using a StyleCritiqueReport schema. The critic provided:

- An

overall_acceptflag and anoverall_score(0.0–1.0) - Per-summary readability scores (for the general summary and each section).

- A brief overview of main readability concerns.

- A list of issues, each specifying the affected summary, category (e.g. clarity, jargon, flow, length), severity, and an optional suggested rewrite that preserved the underlying scientific content.

A style refinement assistant processed the current summaries and the StyleCritiqueReport, selectively rewriting only those sections where the feedback was judged valid. Revisions were constrained to preserve all factual claims, avoid adding new mechanisms or numbers, and adhere to sentence-length targets appropriate for a scientifically literate but non-specialist audience. The final accepted summaries, together with their style scores and iteration counts, were stored alongside the structured report.

Provenance tracking and execution controls

Throughout all phases, the system recorded detailed provenance metadata. For every tool call and LLM invocation, the controller logged the server or model used, input arguments, timestamps, wall-clock duration, and token usage. The provenance model also tracked phase boundaries, critic and style iterations, and whether refinement invoked additional tools.

At startup, the workflow emitted a configuration snapshot including model assignments, tool routing rules, UniProt parsing caps, retry parameters, and prompt-pruning settings, enabling exact reconstruction of run conditions. Tool and LLM retries followed capped exponential backoff strategies to balance robustness against resource use and to prevent runaway execution.

By combining MCP-managed tool access, OpenAI-based orchestration, configurable parsing of primary resources, Pydantic-enforced structural and citation validation, and layered critic/style refinement loops, the system produced transparent, reproducible, and citation-backed gene–cancer assessments suitable for large-scale oncogenomic triage.

References

- Gonzalez-Perez, A., Perez-Llamas, C., Deu-Pons, J., et al. (2013). IntOGen-mutations identifies cancer drivers across tumor types. Nature Methods, 10, 1081–1084. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.2642

- Martinez-Jimenez, F., Muiños, F., Sentís, I., et al. (2020). A compendium of mutational cancer driver genes. Nature Reviews Cancer. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41568-020-0290-x

- MCP Python SDK. (n.d.). modelcontextprotocol/python-sdk. GitHub. https://github.com/modelcontextprotocol/python-sdk

- Augmented Nature UniProt MCP Server. (n.d.). Augmented-Nature/Augmented-Nature-UniProt-MCP-Server. GitHub. https://github.com/Augmented-Nature/Augmented-Nature-UniProt-MCP-Server

- GenomOncology BioMCP MCP Server. (n.d.). genomoncology/biomcp. GitHub. https://github.com/genomoncology/biomcp

- OpenAI Python Package. (n.d.). openai/openai-python. GitHub. https://github.com/openai/openai-python

- Colvin, S. (2024). Pydantic: Data validation and settings management using Python type annotations. Zenodo. https://zenodo.org/records/17253915